...But Mighty

Was this men’s squad from a small service academy somehow (pound-for-pound) the fifth best team at 2025 Nationals?

Ever wonder how a team’s Nationals showing would look if you adjusted it for the size of its undergraduate population?

Well, you are in luck.

‘Pound-for-pound’ means that we divided each team’s points total at 2025 D3 nationals by its undergraduate enrollment. In D3 swimming, you get desensitized to teams from very small schools punching well above their weight. Below is every men’s or women’s team that cleared 100 points per 1,000 undergrads at 2025 D3 nationals.1

Relative to its undergraduate enrollment, no team was more successful at the 2025 NCAA meet than the Kenyon Ladies. The Denison men also had a pretty good meet, winning the national championship despite coming from a school with barely 2,400 undergrads.

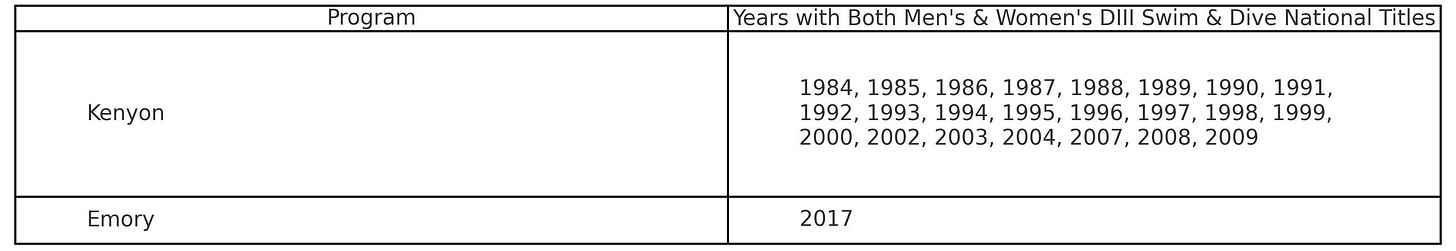

In fact, all four of the top efficiency spots belong to either Kenyon or Denison—not a shocker, given that those are obviously small schools and that, most years, Kenyon, Denison, or Emory (which does have a larger undergraduate population) wins either the men’s or women’s D3 national championship. Occasionally both.2

The Williams women’s team holds a distinctive place in Division III swimming history, having won the first two national championships in 1982 and 1983. They remain a perennial contender—since COVID, they’ve placed fourth three times and never finished worse than sixth. Heading into the 2025 nationals, Williams swimmers held three Division III women’s individual event records.3

The final team on the list is the 2025 women’s national champion: MIT. With more than twice the undergraduate enrollment of Williams, MIT is the largest school featured here. But they made this list by scoring so, so many points. You can handle a bigger denominator when the numerator is pushing 500 points.

So, what is the Coast Guard doing here?

Even by Division III standards, the Coast Guard Academy is small—about 1,000 undergraduates—and demanding. Cadets juggle rigorous academics, military duties, and shipboard training that extends through the offseason. While swimmers at other top Division III programs can train during the summer, Coast Guard athletes spend those months on service assignments, limiting pool time.

Against that backdrop, the Coast Guard men delivered a remarkable 2025 season.

First, there was Colin Twiss. We’ve been fans for a while. Which is irrelevant because we would have had to cover him anyway, because he kept finaling. This year of course he went beyond that, winning the men’s 200 Free. Colin Twiss is the first national champion for the USCGA since Christian Brindamour won the 50 Free in 2014.

Sean Lyman continued his steady rise. After taking fourth in last year’s 400 I.M., he claimed bronze in 2025 with a lifetime-best 3:50.29—a time that would have medaled at every Division III championship on record. Lyman also made the A-final in both the 500 free and the 1,650 free, finishing the meet 10th overall in individual points.

Noah Reice, a sophomore, reached the B-final in the 100 fly and the A-final in the 200 fly. To fill out the relays, the Bears added classmates Kacper Buniowski, Zach McGowen, and Luke Giguere. The six-man squad entered four relays—the 200 and 400 free, 800 free, and 200 medley—scoring big with a 5th-place finish in the 800 free relay and 14th in the 400 free relay.

Small school, heavy obligations, limited training windows—and still, one of the most remarkable performances of last season.

If you want to follow us down a rabbit hole on high school athletics then, by all means, follow the footnote.4

Points Rank – Ordinal rank of total points scored at the 2025 NCAA Nationals. Example: The Kenyon Ladies were the third-highest-scoring women’s team.

Points – Raw team points earned at the 2025 Nationals.

Undergraduate Population – recent undergraduate enrollment for that school.

Points per 1,000 – Size-adjusted performance metric. Examples:

Kenyon Women: 438 pts ÷ (1,752 / 1,000 = 1.752) → 250.0

Denison Men: 463.5 pts ÷ (2,406 / 1,000 = 2.406) → 192.6

Here are those records.

Women’s 1650 Free: 16:21.44 – Sarah Thompson, Williams (3/21/2015)

Women’s 200 Fly: 1:55.66 – Logan Todhunter, Williams (3/23/2012)

Women’s 400 I.M.: 4:13.14 – Caroline Wilson, Williams (3/22/2012)

Of these three, only Ms. Todhunter’s mark in the 200 Fly survived nationals intact.

Sarah Thompson’s 1650 record was broken by Natalie Garre of Bowdoin, who swam a stunning 16:17.84.

Caroline Wilson’s record in the 400 I.M. fell to none other than Williams legend Sophia Verkleeren, who posted a 4:11.23.

In high school athletics, the number of students attending the school is the strongest determinant of the school’s athletic success.

There are exceptions that readily spring to mind, like the story behind the movie Hoosiers. But the reason that story is so captivating is because it is so unlikely. A study of the results in the Indiana men’s high school basketball tournament—the setting for the Hoosiers story—found “the relative size of the student body is the most consistently important factor in tournament success.”

Competitive imbalances created by disparate school sizes are very much on the mind of the associations that oversee high school sports. A couple of minutes of googling turned up these results from Virginia and Ohio:

Virginia High School League moves toward six classifications, Washington Post, Jan. 6, 2012 - ‘The task force wants to fix what it and many member schools consider to be problems with the current system — the enrollment disparity within the A, AA and AAA classifications, and at times gaping enrollment differences among teams competing for the same championships.’

OHSAA board of directors votes to increase number of divisions in seven sports, WCPO, Feb. 15, 2024 - ‘For too long, the largest schools in our divisions have been so much larger than the smaller schools in the same division, which has resulted in many schools accepting that they realistically have little chance at making a run in the tournament.’

The other obvious driver in sports success at the high school level is the affluence of the families that send their kids to those schools (the link takes you to a post on the site of the American Association of School Administrators, in which they cite this study).

This same study found that ‘schools with a lower percentage of students eligible for NSLP are more successful in the tournament.’ NSLP stands for the national school lunch program, and the percentage of students at a school qualifying for NSLP is a handy way to gauge the number of students coming from families at or below 130 percent of the federal poverty level.

This conforms to common sense.

Cost barriers shrink rosters: Fees and equipment costs push low-income students out, cutting the overall talent pool at cash-strapped schools.

Year-round development favors the wealthy: Club teams, private lessons, and elite travel tournaments—often costing thousands—accelerate skill growth for students who can afford them.

Better-paid coaches & support staff: Affluent communities fund higher stipends, full-time strength coaches, and certified athletic trainers, delivering safer, more sophisticated programs.

Superior facilities & technology: Turf fields, indoor practice space, video analysis, and rehab rooms raise training quality and reduce injury downtime, advantages that booster clubs can bankroll.

One intriguing possibility raised by this observation is that high poverty has a negative effect, but that further wealth effects are not otherwise obvious. This suggests that (perhaps) once a program reaches an adequate funding baseline, additional wealth yields diminishing competitive returns, while schools stuck below that line remain at a steep disadvantage.

I believe it is important to also point out the limitations of the smaller schools in terms of majors available, resources and graduate programs. This has been especially true in the post-pandemic period when 5th years were very scarce at Kenyon, Denison, Williams size schools (and Coast Guard) and where MIT, NYU, Emory and other larger universities with sizable graduate programs prospered. Even from a straight recruiting point of view, these schools, especially like Chicago which tends to use its "pipeline" into their med school as a recruiting tool, have distinct advantages. The fact that Kenyon, Denison and Williams have been so consistently successful with their small enrollments and limitations is quite impressive.

Point number 4 for high schools is spot on! The vast majority of the team if not the entire team in HS is just made up from the student body, without any recruiting. Just the opposite of college.