Nationals is intense. We are exhausted and way behind on emails and the dog would really like a walk. And we are sure that the athletes returning to campus after grueling travel, only to face a mountain of homework, are crying a tear for us right now.

We will get into the fun stuff in the coming weeks:

We will admit to being baffled by what ‘Swimmer of the Year’ actually means.

We will look at the top point scorers at Nationals.

We will recap the record breakers, or at least rank those who came closest to breaking a record.

We will KSO+ score the season’s swims - including Nationals - to evaluate which swims were furthest above the average of fast swims over the past 10 seasons.

But first we have to talk about Kristin Cornish.

When we talk about distance, we mean the 1650. We understand that the 500 Free feels distance-y, and that’s fine. Ms. Cornish made this easier for us by simply winning the 500 Free at Nationals with a season’s best time - 4:48.38. It is a solid time, basically good enough for top three in any year in Division III history, and would have won the event in about half those seasons.

Kristen Cornish did something unprecedented this year

Kristin Cornish broke 16:30 twice in one season, and came within 0.05 seconds of doing it a third time. Here are her 1650 times from this year:

16:29.78

16:29.52

16:30.04

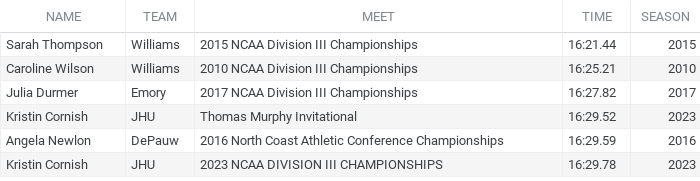

Here is the full list of every swim under 16:30 by a Division III athlete swimming the Women’s 1650:

That’s all of them. Every single one. Dating back to the founding of Division III.

Want to see a complete list of every Division III athlete - who more than once in a season - swam the Women’s 1650 under 16:30:

Kristin Cornish

Want to see a complete list of every Division III athlete - who more than once in their entire NCAA career - swam the Women’s 1650 under 16:30:

Kristin Cornish1

The greatest Division III distance swimmers before Ms. Cornish swam the mile several times a year, up to twelve times in the course of their career. None of them broke 16:30 twice.

Now we have Kristin Cornish. She did it twice in five tries. And she was .05 seconds away from doing it three times.

What about the record?

The Division III record for the Women’s 1650 - 16:21.44 - was set by Sarah Thompson (Williams) on the last day of her NCAA career, March 21, 2015.

It is an impressive record.

Still, it is also true to say that Ms. Thompson gave us the fastest version of what we had seen before: a once in a career outlier swim that doesn’t neatly fit with other performances by that athlete.

Every one of the athletes with times faster than Ms. Cornish’s current best had a downside variance that Ms. Cornish is yet to show.

Here are the average times (in seconds) of all the NCAA mile swims from the 20 fastest Women's 1650 swimmers in Division III history.

The picture is even clearer if you focus on the first years of Ms. Thompson’s career compared to Ms. Cornish.

Obviously, Ms. Thompson was very fast. But Ms. Thompson never had a year where her average swim was as fast as Ms. Cornish’s first year average (by far the weaker of Ms. Cornish’s two years in Division III swimming). And Ms. Cornish’s slowest swim this year is faster than any swim from Ms. Thompson, except for the outlier.

It is tempting to play it safe and say ‘yeh, Sarah Thompson still has the record, but Kristin Cornish might be the best by the time she is done.’

But we don’t think that is an honest read of the data. We think the evidence is clear. Kristin Cornish is - right now - the greatest mile swimmer in the history of Women’s Division III.

All other athletes in the history of Division III have produced only four swims faster than Ms. Cornish’s 2023 average swim in the Women’s 1650. And every one of those outlier swims was produced by an athlete who did not replicate that time, or even just get reasonably close, ever again.

Ms. Thompson was a terrific swimmer and there is no denying that her record time is the fastest anyone in Division III has ever swum the Women’s 1650.

But that might be all that swim tells us. Its singularity, and end-of-career timing, undermines many of the things we want records to mean. Outliers (especially end-of-career outliers) don’t tell you what to expect next from that athlete.2 And outlier records (regardless of timing) can’t tell you which athlete was the best at that event.3

But the grinding regularity of Ms. Cornish’s excellence sends one clear message: she’s already the best we have ever seen.

We guess you could argue that 16:30 is an arbitrary standard, but you'd have to admit it is a pretty good one. Only five athletes in the history on Division III ever swam a race that met that standard and, well, none ever did it twice. In their entire careers. Except Kristin Cornish.

If it is an arbitrary standard, then it is one that seems to sit at the exact right place to separate truly outstanding performances from the merely very good.

It is also the case that 16:30.06 is exactly three standard deviations from the average of the 100 fastest swims in women’s 1650 from each of the past five full seasons. In other words, 16:30.06 is worth 3 SRS points. This is not about taking an arbitrary time-point and making that the standard; there is nothing arbitrary about pointing to a performance that is three standard deviations above the average of other competitors and using that as your standard of excellence.

And if we were to use this seemingly less arbitrary standard - 3 standard deviations from the average of the top 100 swims from each of the past five full seasons - then Kristin Cornish would have broken that barrier THREE times in 2023. Because her near miss with 16:30 (16:30.04) was near enough that it is still worth 3 SRS points.

Partly because, well, that whole ‘end of career’ thing. It is useful when these records tell us what to expect next from that athlete. Not useful if the athlete immediately retires.

Mostly when we say ‘records tell us what to expect next’ we mean something like this: think about, say, Aaron Judge. His record offense performance last season creates an expectation - whether it pans out of not - of more very-high-level offensive performance. Records tell us what to expect next.

More baseball. Think of Joe DiMaggio’s hitting streak. In 1941, Yankees Center Fielder Joe DiMaggio hit safely in 56 games in a row. Even at DiMaggio’s elite skill level, such a feet is very very unlikely for any player.

So it was an outlier, in more than one sense. For instance, by all accounts, Ted Williams was a better hitter in 1941. Better than DiMaggio, better than everyone. This is quantifiable, whether you want to use Baseball Reference OPS+ or Fangraphs WRC+, or even Fangraphs WAR, Williams was just better.

But Williams had no such streak. Why would the better hitter not have the longer streak? Because a batting streak of that length is an outlier record. And outlier records do not necessarily accrue to the best performer. They are probably more likely to accrue to someone who is very good but not the best. Because there is only one ‘best,’ but several ‘very goods’. And given that there is some randomness is the distribution of such outlier records, it is simply more probably that such records will attach to someone in the larger pool of ‘very good’ performers.

This is not about statistical nihilism. There is some data that suggests who really is the top performer. And that data has more to do with who performs near the top most consistently. Ted Williams is the greatest hitter of that era. And that is as much because of his lows (his lows were very high) as because of his highs (his highs were high too, if not always the very highest by all measures). It was the grinding regularity of Williams’ offensive performance that identifies him as the best.

One last baseball example:

Hank Aaron was on of the 2-3 greatest home run hitters of all time. He played 23 years and hit 755 home runs. His most prolific year for home run hitting was 1971, when he hit 47 home runs in one season.

Brady Anderson had a good career and one spectacular year - 1996 - when he hit 50 home runs. He never again hit more than 24 home runs but was a productive player for a long time, a very good baseball player.

Arguing that Sarah Thompson’s one outlier swim makes her a greater distance swimmer than Kristin Cornish is kind of like arguing that Brady Anderson was a greater home run hitter than Hank Aaron, because Hank Aaron never hit 50 home runs and Brady Anderson did.

This is a pretty arbitrary metric... it's not like Sarah Thompson and her coach sat down at the beginning of the season and said "hey, let's see if we can get a best-average mile time under 16:30 with 3 swims this season!" In fact, NESCAC teams dont even have a midseason invite, and Thompson was so fast that with an NCAA invite assured, would have had no reason to do a full taper for conference.

There are of course schools of thought that this all should change, and metrics like the one you have chosen here should be more of a focus. Radical ideas like individual event conference titles being awarded on the basis of a best average of swims across a season rather than a single performance... Team titles by dual meet records rather than a single champ meet... National invites by best average times. I personally love these ideas - I think the whole thing about the sport of swimming where you slog it out for 6 months and put all your eggs in one basket at the end of the road is simply no fun at all, and the sport could be way better off and more exciting if you had more competitions that actually meant something. (ISL is a good example of something more like this). That said, that isn't happening any time soon, sadly. And until it does I don't really think its fair to say that one athlete was a better swimmer than another for being more consistent within a season. That's just not what any of them are even trying to do.

No argument here. She’s amazing!